Mexican law allows abortions for victims of rape – but state hospitals and politicians often stand in their way

Por Dánae Vílchez y Verónica Martínez

openDemocracy / La Verdad

Mexican federal regulations to provide emergency abortion services to victims of rape are being systematically flouted by state government health workers and law enforcement bodies in regions bordering the United States, an investigation by openDemocracy and La Verdad de Juárez has found.

Federal regulations permit women and girls to have an abortion if they are victims of rape. But hospitals and police in northern Mexican states – where there is a growing rate of sexual violence and high prevalence of underage pregnancy – stop abused pregnant women from taking control of their healthcare decisions, say medical sources and rights advocates.

In 2022, more than 9,000 14-year-old girls (the age of consent varies from state to state, but the youngest is 15) gave birth in Mexico, and there were more than 56,000 reported cases of sexual abuse and rape. In 2022, a 13-year-old girl in Chihuahua state was denied an abortion. Another 13-year-old suffered the same fate in the state of Sonora in 2016.

“They [medics] are always looking for ways to stop [abortion] from happening; they use all their resources not to guarantee it,” said Karina de la Cruz, a member of the feminist group Marea Verde in Sonora’s largest border town of Nogales.

In 2021, the Mexican Supreme Court ruled that criminal penalties for terminations were unconstitutional. And in September 2023, the same court decriminalized abortion nationwide, opening the door for the federal healthcare system to provide abortions.

However, at the moment, individual states are responsible for implementing their own legal changes, and the speed of this can be dependent on political climate. Twelve of the country’s 32 states have legalized abortion up to 12 weeks, including the border states of Baja California and Coahuila, but in the other northern states abortion is highly restricted.

In Chihuahua, Nuevo León and Sonora, abortion remains a criminal offense despite the Supreme Court ruling, punishable by imprisonment: a year behind bars in Nuevo León, five in Chihuahua and six in Sonora. Exemptions are allowed in cases of rape and if the pregnant woman’s life is at risk, but only Nuevo León considers other health risks. Chihuahua and Sonora place responsibility for any pregnancy loss on patients, so those who experience miscarriages can be “culpable” or suspected of “negligent conduct”, though in practice they are rarely if ever sent to prison.

Reproductive rights advocates claim that lawmakers in these states are dragging their feet over bringing local laws in line with the Supreme Court. Official statistics show that criminalization remains high.

Conscientious objection and abortion

A federal decree (NOM-046) makes it mandatory for public and private hospitals and clinics to provide healthcare to assist victims of domestic, gender and sexual violence (including children and adolescents) – including emergency ‘morning after pill’ contraception and abortion. But compliance with the law is marred by religious convictions and prejudice among medical staff, according to Nora Villa Baca, professor of legal and forensic medicine at the Autonomous University of Chihuahua.

Healthcare staff can legally refuse to engage in practices that conflict with their moral or religious views – in Mexico, this usually means abortion. It’s a voluntary process whereby they register as a conscientious objector, or a non-objector.

But it’s difficult to find staff in the public healthcare system who will openly declare they are willing to carry out abortions because they are targeted and stigmatized by colleagues, said Villa Baca. “They are branded ‘baby killers’. This affects the person who performs the procedure,” she said.

“When I work in the public health sector, my personal religious beliefs should not influence my care for patients,” she added. “The state has the responsibility to help the woman to recover her health… If there is sexual violence, this includes the consequences it may have, such as a sexually transmitted disease or an unwanted pregnancy.”

In 2021 the Supreme Court specifically limited the use of conscientious objection in relation to abortion. Conscientious objection “is not absolute” and shall not be used to deny fundamental rights, such as access to abortion for a person who was raped, the court said.

Abortion for a rape victim is defined as emergency care, thus removing it from the procedures that a conscientious observer can object to performing, according to Alfonso Carrera, medical director of Fundación MSI (which is affiliated with the international network MSI Reproductive Choices).

Statistics suggest the reality may be different in public health centers in the northern states.

In Chihuahua, authorities did not respond to our repeated requests for information about abortion services and conscientious objectors. But according to the National Centre for Gender Equity and Reproductive Health, only 24 abortions were performed (on patients aged 11 to 32) between January 2019 and March 2020. For comparison, abortion support group Aborto Seguro Chihuahua claims that it assists an average of six women seeking abortions every day.

In Sonora, state officials said there are no records of conscientious objectors working for the healthcare system, while 101 staff have self-declared as non-objectors. Despite multiple requests by openDemocracy, the health secretariat refused to reveal the total number of medical staff. For the first four months of 2023, the state reported 55 “pregnancy losses”: four terminations following sexual violence, and 51 attributed to “negligent conduct” (meaning a miscarriage).

In Nuevo León, the health authorities told us that 43 medical professionals are registered as objectors and 25 as non-objectors. Twelve abortions were performed in the first seven months of 2023 – ten for rape, one because a pregnancy was life-threatening, and one because it posed health risks.

Baja California health authorities said there were no medical staff registered as conscientious objectors.

Little training, lots of red tape

Doctors say unequal access to reproductive options can be blamed on federal authorities’ reluctance to push states to enforce abortion regulations.

“A legal framework is in place, and there are doctors that can perform [abortions]. But there is no will from the authorities,” César Ruiz, who runs Medieg Health Services, a private reproductive health clinic in Mexico City, told openDemocracy.

Lack of training in gender perspectives widens the gap between regulations and real access to services, according to Ruiz. “The federal government should have compulsorily trained all medical staff on NOM-046,” he said. But he added: “If you ask any healthcare staff what NOM-046 is, they don’t know.”

State authorities add several hurdles to women wanting abortion. In Chihuahua, hospitals frequently require a police report on the sexual assault, according to lawyer Laura Dorado, an activist for reproductive rights and the co-founder of Aborto Seguro Chihuahua, even though these are not necessary according to federal regulations.

Dorado said her group had been able to establish “a good channel of communication” with health professionals in order to guarantee abortion services, but that “they’ll often find a negative response” if the pregnant person has passed the 12-week time limit. Abortions after 12 weeks have been denied in the state, even for minors or victims of rape, for whom federal decree NOM-046 says there should be no time limit on abortions.

Andrea Sánchez from Aborto Seguro Sonora said protocols for the care of victims of sexual violence are not always followed in Sonora. “When women seek these services, medical staff sometimes say abortion is illegal even in the case of rape,” she said.

A health ministry official, who openDemocracy has agreed not to name, said the referral process for reaching a public hospital where abortions are performed can be long and bureaucratic. By the time the patient has got through all this red tape, they are usually more than 12 weeks pregnant, beyond the deadline for legal abortions.

The official added: “Staff and facilities offering [abortion] services are limited. There are towns that lack trained staff, or lack them on all shifts, though they should be available at all times.”

Sonora’s Ministry of Health told openDemocracy it had trained 271 staff in the NOM-046 guidelines and that it offered abortion services at the General Public Hospital in Hermosillo, the state capital. The state is home to almost three million people.

This lack of services is even more acute when private medical facilities fail to follow the law on emergency abortions.

In Baja California, which is less restrictive having legalized abortion in 2022, terminations are available at three public clinics, in Mexicali, Tijuana and Ensenada, according to reproductive rights group GIRE. But despite the federal and state legal framework, most private providers deny access to abortion in cases of rape, according to Carrera of Fundación MSI.

Carrera says his group’s clinic in Tijuana, Mexico’s second-largest city with a population of over two million, is the only private facility in Baja California providing abortion services.

Feminists fight criminalisation

Although the Supreme Court ruled in 2021 that criminalizing women for abortion was unconstitutional, state governments continue to prosecute such cases. Nationwide, there were 819 criminal cases in 2022, compared to 704 in 2021. In the first five months of 2023, 449 new cases were opened.

In Sonora, at least six women are behind bars for having had an abortion. Nine prosecutions were launched in 2022, and seven this year so far, according to official data. In Nuevo León, 71 new criminal cases involving abortion were opened in the first six months of 2023, while the previous year saw 144 investigations. In Chihuahua, ten cases were opened in 2022, and three up to June this year. Even in Baja California, 43 investigations were opened in 2022 and another 12 up to June 2023.

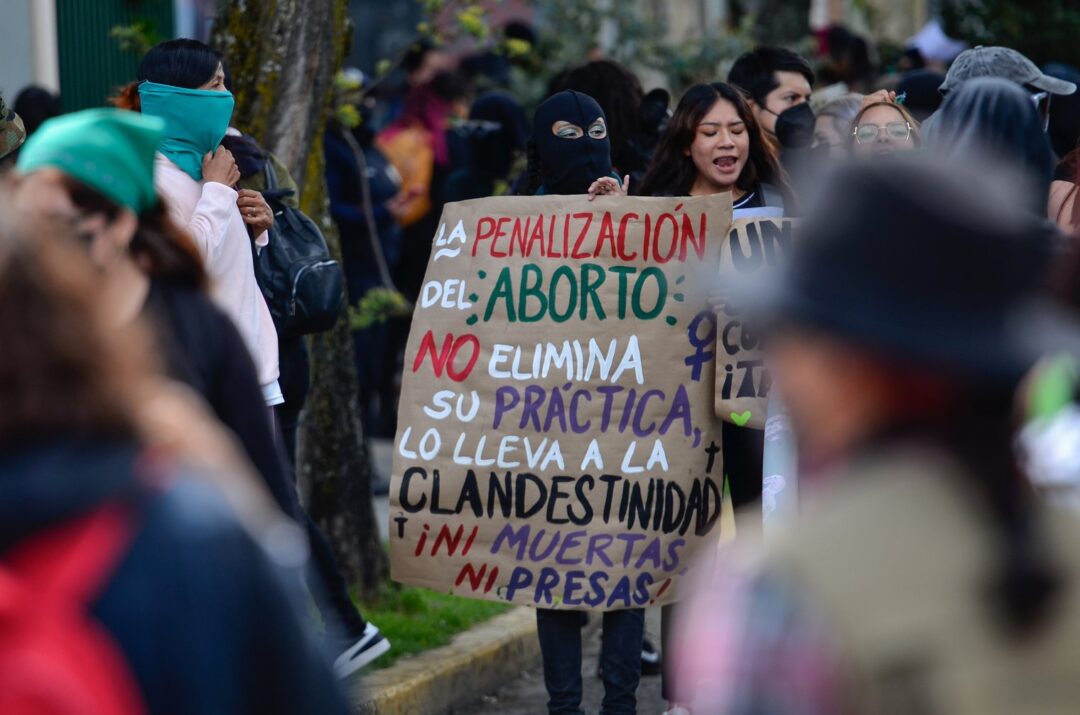

| Meliza Valencia/openDemocracy. All rights reserved

In the border city of Nogales in Sonora, activist Karina de la Cruz explains how she helped a rape survivor have an abortion using medication. When the woman went to hospital for post-abortion complications, she faced strong disapproval.

“A gynecologist harassed her to confess she had had an abortion. The doctor threatened her with reporting her case to the public prosecutor’s office,” De la Cruz said. “The girl was very scared, but she stuck to her line of saying: ‘No, I didn’t do anything,’ and eventually they left her alone.”

Conservative politicians are ultimately the cause of this continued criminalization, say feminist activists working to expand reproductive choice.

Chihuahua governor María Eugenia Campos – who wore the anti-abortion movement’s light blue scarf on her first public outing – and most lawmakers in the state are conservative. An initiative to legalize elective abortions up to 12 weeks remains “frozen” in Congress, according to Mariela Castro from Marea Verde Chihuahua.The governor “made it clear that there would be a sustained battle against the pursuit of our rights,” Castro said.

But Marea Verde and Aborto Seguro are fighting back in court. They have introduced 70 filings seeking judicial orders for abortions – which will mean that named women, although not pregnant at the moment of filing, can use the protection if in the future they decide to have an abortion. Several have been granted by local courts; in March, one reached the Supreme Court.

These organisations, supported by a civil rights legal group called AbortistasMx, are preparing a collective writ of protection – a legal action allowing people to challenge authorities that they believe are violating their rights – asking the state authorities and hospitals to fully enforce NOM-046. They have so far collected around 312 signatures.

In Chihuahua, the groups have led a state-wide campaign involving 13 collective writs, with seven already granted – effectively meaning state courts have accepted the protection of abortion rights. With 24 signatures issued per collective writ, 168 people are protected and 144 more are awaiting the court’s resolutions.

However, some states are pushing back on abortion rights.

Nuevo León amended its constitution in 2019 to protect life from conception, a move that was overruled in 2022 by the Supreme Court, as states lack the constitutional reach to define personhood and the beginning of human life. But state governor Samuel García has again urged congress to include this definition in a fresh round of constitutional reforms.

Feminists who provide abortion pills in the state capital, Monterrey, are unafraid of local restrictions to their work, believing federal legislation such as NOM-046 will ultimately protect them.

“We don’t feel threatened by these legal issues,” said Vanessa Jiménez from feminist group Necesito Abortar. “This is a right, and we are going to defend this right, and women need to [embrace] the right to choose about their own bodies.”

Pingback: Regulación federal sobre aborto es letra muerta en estados del norte de México – La Verdad Juárez